Print is it

If you’re a professional photographer, selling prints ensures the success of your livelihood.

• July 2016 issue

Memories are best preserved in tangible form

About two years ago Allison Tyler Jones, CPP, received a telling phone call. “I just really want a real photographer,” the woman on the line told Jones. “I have all these pictures on my computer and I want one on my wall.” The woman had recently visited her sister’s home, noticed a new wall portrait, and asked her sister where she’d had it printed. When her sister said the photographer had printed it for her, she was surprised. “Who is the photographer who would print that for you? she’d asked her sister,” says Jones. “Twenty years ago that question would have never been asked. Photographers always did that.”

As “shoot-and-burn” photography has become more prolific and consumers have become increasingly addicted to the images on their social feeds, printed photography has become more rare. That’s not a good thing—not for society and not for the photography profession. “We’re being dubbed the ‘lost generation’ because as a whole we’re printing and preserving our histories less and less,” according to PPA Director of Education Angela Kurkian, M.Photog.Cr., CPP. “Relying on electronic ways to view and archive our images, we may be endangering our entire personal visual history.”

That’s because digital eventually fails. And just as important, it’s difficult for a photographer to cultivate a lucrative and sustainable business by selling digital files exclusively. In the past, “Photographers had access to professional labs and products that weren’t widely available to the general public,” says Kurkian. “Now almost anyone can find reasonable products on the market that are, in their opinion, comparable to those products.” Photographers need to differentiate themselves, she says, and one way to do that—and to be most profitable—is to provide printed photographs.

“Digital files are a commodity,” agrees Jones. But a fine-art print on an 8-ply mat, framed and signed by the photographer—there’s no digital equivalent. “There is really only so much you’re going to pay for a commodity. A finished piece of art on the walls of your home is a different price point.”

See it through

Like many photographers who’ve launched studios in the past decade, Jones began with a shoot-and-burn business model. “When I very first started, I was like, I don’t want to mess with print. Who wants to deal with prints, and what’s wrong if I don’t want to?” But then a friend who’d been in the business longer than Jones made a good point: You’re leaving a lot of money on the table if you don’t sell prints.

After six months of selling digital files, Jones saw she was working herself to the bone for little return. Clients were calling constantly asking for retouches after they’d attempted to make their own prints even though Jones hadn’t included that work in her rate. “We think there’s an easy way to make money—I have this camera and I take digital files and I take no responsibility. But the second somebody gives you one penny, they have expectations for you. You might think, Get off my back. I only charged you a hundred bucks. But in their mind, they think, I have paid you; you better make me look great.”

What ultimately pushed Jones to rebrand as a print artist were her clients. She went to one client’s home and saw a horrendous green-tinged print on their wall that they’d had made at Costco, she says. Worse, that client had told friends and neighbors that Jones made the photo. One day a client called her from a drugstore and requested a different cropping of a portrait because they couldn’t print it the way they wanted. She says, “I thought, if I’m going to mess around with cropping, then I’m taking it to the end and I’m going to make it look like I want it to look and not how they think it should look. I am taking responsibility for the work.”

Transitioning to a full-fledged print artist happened in stages. “At first I was not letting anything go out of the studio that wasn’t a finished product. Then I was not letting anything go out of the studio that wasn’t framed. And then we went to delivery, to having it installed, and built that into the cost of what we do. It comes down to taking on more responsibility. In every industry—graphic design, interior design, art—the more responsibility you take on, the more you can charge. When you just shoot-and-burn, there is a threshold that you can’t really go beyond.”

“Just the capture is only a quarter of the job,” she says. “The capture and the retouch is half the job. To me, printing, framing, and installation are the completion of the work.” The end result for Jones: Her profits have increased 10-fold.

Print strong

Sticking by print isn’t always easy, Jones notes. It was a struggle at first because competitors were selling digital files and consumers didn’t know they should expect more. “Finally I just realized that I can only build a business how I see it, how I feel like it needs to be done. What I want you [the client] to have is something on your wall, a cool piece of art that happens to be you, your siblings, and your mom and dad … an amazing fine-art print that you can hand down to your kids.”

Let’s face it, there is no such thing as a digital heirloom. Tim Kelly, M.Photog.Cr., F-ASP, who’s been making prints by hand for 50 years and was an early adopter of digital photography, can vouch for the ephemeral nature of digital files. “I myself have had image files from the early ’90s that were stored on optical disc drives, Zip and Jaz drives, DAT tapes, DLT tapes, Kodak Pro CDs—you name it. Those storage mediums are dead and gone. In the professional world we spare no expense to safeguard our images, yet there are plenty of them that we can no longer retrieve from their original media. We have whole shelves of hard drives that we had hermetically sealed. They don’t run anymore. There are dozens of years of CDs that you would be lucky to retrieve a file from.”

The safe bet is always going to be print, he says. “Having the print that you really wanted, whether it’s a professional portrait on the wall or an album of an event like a vacation or a baby’s first year—all that has to be in a tangible format. It can’t be digital.”

Consumer buy-in

In a world where some photographers are delivering just digital files, and more consumers are glued to their phones and computers, the importance of print can be a hard sell. But the right clients are out there, and branding yourself as a portrait artist goes a long way toward connecting with clients who appreciate and understand the importance of your product, says Lesa Daniel, Cr.Photog., of Gregory Daniel Portrait Artist. And selling prints is simply the right thing to do, she adds. “They’re in the consumer’s best interest.”

“Prints are important because it increases self-esteem for children to see their portrait hanging on a wall,” Daniel says. “It has been proven in psychological studies that they feel more connected, and it helps them know they’re important in that family. So I think that alone is a good enough reason to print something.”

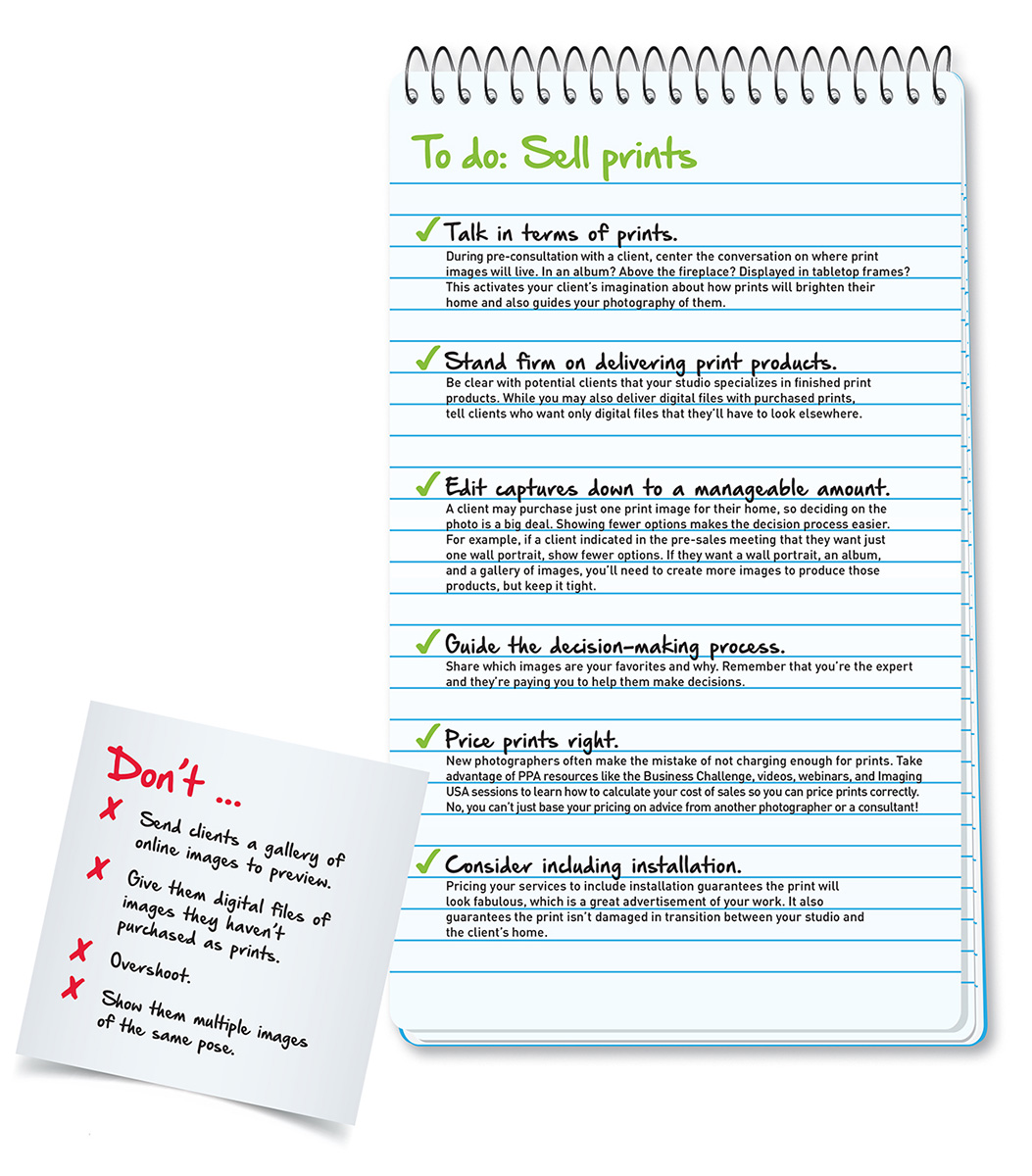

Still, notes Jones, many potential clients ask the same question: Do you sell digital files? She always answers the same way: “Tell me more about that.” They usually tell her they want to post pictures on social media, in which case she assures them that any prints they purchase will also be made available in digital form suitable for social media. If they tell her they want to print their own holiday cards and canvases from Costco, she takes a different tack. “I say, We specialize in finished products. We are going to print your images 15 times if we have to, to get it perfect. We are going to bring it to your house and hang it on your wall. But if you don’t need that level of service then you don’t need me.” It can be hard say that to a potential client, she admits. “You have to be willing to sit with that and be OK with that.”

In-person sales is the only way to go to sell prints, according to both Jones and Kelly, who never send clients an online gallery prior to a face-to-face meeting. “I don’t think the photographer should allow for that emotional fulfillment prior to getting their sale,” Kelly says. He meets with clients, helps them make selections of the prints they want and in what form, and after that purchase he gives the client watermarked digital files of purchased prints for use on social media. “We are quite all right with that because that image is not a flash in the pan. It represents a print that they own,” Kelly says.

For the sales meeting, both photographers edit selections to a minimum so clients aren’t overwhelmed by too many choices. A senior portrait session of perhaps 150 images gets whittled to 40 to 50 for album selection, says Kelly; a family session gets whittled to fewer than 30 for wall portrait selections. “Nothing kills your sales faster than too many images,” agrees Jones, who doesn’t retouch until after selections are made. As a result, clients truly don’t see the completed image until it’s printed, framed, and installed in their home. And that’s just as Jones desires it. “I started in the dark room and I love print and I have always loved print,” she says. “I don’t want to do it any other way.”

Amanda Arnold is the associate editor of Professional Photographer.